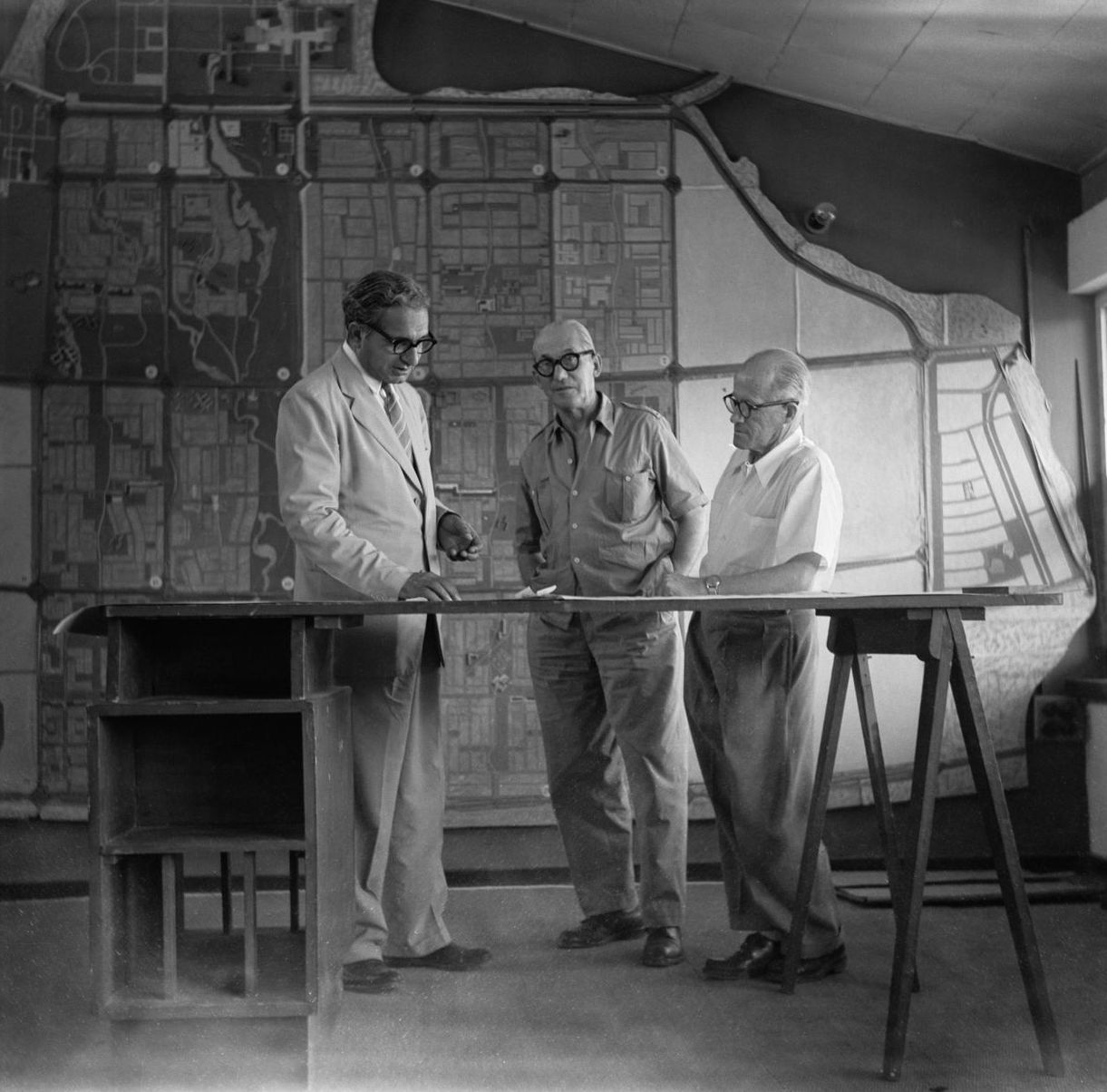

Parmeshwari Lal Varma, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, photographed c. 1950’s.

Photo by Jeet Malhotra, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

In the grand tapestry of 20th-century modernism, certain figures command the spotlight, their names echoing through the chronicles of design history with an almost singular resonance. Among them, Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, universally known as Le Corbusier, stands as an architectural titan. Yet, in his colossal shadow, another, more understated force operated, a man whose contributions were no less vital, though often less heralded: Pierre Jeanneret. Born in Geneva in 1896, Pierre Jeanneret (1896-1967) was a Swiss architect and designer whose immense impact on modern architecture and design is only now being fully appreciated, revealing him not merely as an associate but as a driving force and a visionary in his own right. His narrative is one of understated brilliance, a testament to the persistent power of design that transcends fleeting trends and superficial accolades.

Early Collaborations and Modernist Roots

Jeanneret’s formative years laid the groundwork for his distinctive approach. After graduating from the Geneva School of Fine Arts in 1921, he moved to Paris, where he swiftly became Le Corbusier’s closest associate and business companion. This collaboration, described as a profound and life-long professional relationship, was instrumental in shaping the nascent modernist movement. Their shared vision found its voice in the 1926 manifesto, ‘Five Points of Architecture,’ a foundational text that articulated their architectural aesthetic. Beyond theory, their partnership extended into the tangible realm of furniture design, notably with Charlotte Perriand from 1927 to 1937. Together, they embarked on the innovative project for ‘l’équipement d’intérieur de l’habitation’. Jeanneret’s particular aptitude for the more technological elements and his frequent drafting of the first blueprints for pieces like the tubular steel chairs exhibited at the 1929 Paris Autumn Salon underscore his crucial role in translating abstract concepts into concrete forms. This early immersion in the practicalities of design, particularly in furniture, was not merely a technical exercise; it was a forge that refined his ability to seamlessly blend functionality with aesthetic clarity. This period demonstrates that his immense artistic sensibility was not a later development but was honed through the very act of making, laying a robust foundation for his later, more independent expressions.

The philosophical underpinnings of Jeanneret’s work were evident from these early collaborations. Their structures were keenly thematically linked to the idea of Synthetic Cubism, an artistic movement characterised by a shift towards compositional relationships and fragmented subjects within geometric frameworks. This intellectual engagement with avant-garde art movements speaks to an artistic depth that extended far beyond mere structural engineering. What is particularly noteworthy is that Jeanneret’s early tubular steel furniture, unlike the often austere and unyielding pieces emerging from the Bauhaus, possessed a sensuous, relaxed, and welcoming look. This subtle yet notable difference indicates an innate artistic inclination towards human comfort and warmth, even within the rigorous geometry of modernism. This suggests that from the outset, Jeanneret’s artistic sensibility was truly rooted in the human experience, prioritising inviting forms and comfort. His designs were not solely about efficiency but about enriching daily life, foreshadowing the empathetic and contextual approach he would later master in India.

A pivotal moment that truly forged Jeanneret’s independent thought arrived in 1940, when his partnership with Le Corbusier fractured. This schism was born from immense ideological differences over the war: Jeanneret’s principled decision to join the French Resistance stood in stark contrast to Le Corbusier’s controversial collaborations with the Vichy regime. This period of independence proved transformative. Jeanneret established his own firm in Grenoble, embarking on groundbreaking research with fellow designer Jean Prouvé into new concepts for prefabricated housing. The F 8×8 BCC Demountable house (1941) stands as a powerful testament to their ingenuity, showcasing an extraordinary ability to adapt to extreme wartime conditions by optimising materials and construction methods. The political and ideological divergence was more than a personal conflict; it was a catalyst for Jeanneret’s independent artistic and ethical development. Forced to navigate a world of material scarcity and moral choices, his work with Prouvé instilled a fervent sense of resourcefulness, adaptability, and a commitment to socially responsible design. This period, driven by necessity and personal conviction, was crucial in shaping the raw and radical and inherently sustainable approach that would later define his work in India. It was during this time that he truly began to break away from European architectural dogma, developing a unique artistic voice rooted in pragmatism and human need.

The Indian Canvas: Chandigarh as a Testament to Integrated Design

The mid-20th century witnessed an immense shift in global geopolitics, and with India’s hard-won independence, a new nation sought to articulate its identity through monumental acts of creation. Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, envisioned a new capital for Punjab – Chandigarh – not merely as a city, but as a potent symbol of modernised India, unburdened by its colonial past and reflecting a fervent commitment to progress. This was an audacious statement of national aspiration, and it was to Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret that the formidable task of manifesting this vision was entrusted.

Following their post-war reconciliation, Le Corbusier and Jeanneret received the monumental Chandigarh commission around 1950-51. While Le Corbusier, the grand visionary, spent relatively little time on the project or even abandoned the project mid-way, it was Pierre Jeanneret who moved to Chandigarh in 1951 and remained for an extraordinary fifteen years, until 1965. His unwavering presence saw him assume the mantle of Chief Architect and Designer of urban redevelopment and Town Planning Adviser to the State of Punjab. He provided crucial on-the-ground supervision for the iconic Capitol Complex, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Beyond these grand designs, Jeanneret was responsible for a vast array of programmes, from individual and collective accommodations for all social classes to schools, university dormitories, hospitals, and the city library. He also designed notable public buildings like the Governor’s Palace, State Library, and City Hall, and most famously, the Gandhi Bhawan building on the Punjab University campus, which evokes a lotus flower floating on the water. The stark contrast between Le Corbusier’s transient involvement and Jeanneret’s decade-and-a-half residency in Chandigarh is more than a logistical detail; it is a testament to Jeanneret’s unique artistic and humanistic approach. His choice to live in the city, design his own home there, and ultimately have his ashes scattered in Sukhna Lake upon his death signifies an unparalleled personal and spiritual commitment. This intense immersion allowed him to understand the nuances of the local context and the daily lives of the inhabitants, directly informing his designs. It elevates his contributions from mere functional problem-solving to a form of social art, where the architecture and furniture are imbued with empathy and a profound sense of belonging. This personal narrative is central to understanding how his work transcended utility.

Jeanneret’s approach in Chandigarh was truly empathetic; he embraced a genuine Indian perspective and was sincerely in touch with the country and its rituals. He meticulously sought to understand the specific conditions of building in India, including the imperative for low budget projects, ease of implementation, and speed of execution. His designs were inherently climate-responsive, featuring cool areas shaded by verandahs and porticos, and transversal ventilations to ensure comfort in the hot season. He consciously utilised local materials and components of his Indian architectural vocabulary, such as river pebbles, brick screens, and white-washed surfaces. Beyond materials, he invested in human capital, training young Indian architects and fostering a local design bureau. His reputation as “Nehru’s friend” and his genuine admiration by Indians cemented his unique position. This domestic and human-centric approach, born from his engagement with local villages, stood in contrast to Le Corbusier’s more institutional style. Jeanneret’s intense cultural immersion and practical understanding of India’s climate and resources were not merely practical considerations but integral to his artistic vision. His focus on low budget projects, ease of implementation, and speed of execution, combined with climate-responsive designs and the empowerment of local craftsmen and architects, demonstrates a holistic, socially conscious artistic approach. This transforms his functional designs into a powerful artistic expression of empathy and cultural synthesis. It challenges the notion of a monolithic modernism, proving that design can be both globally relevant and truly rooted in local identity, making his work an immense statement on contextual and humane architecture.

Jeanneret’s influence extended far beyond the capital city of Chandigarh. He directed city planning and architectural projects in various other Indian townships, including Talwara in Punjab; Sundernagar, Pandoh, and Slapper in Himachal Pradesh; and the Medical College at Rohtak in Haryana. These projects, often overshadowed by the monumental scale of Chandigarh, underscore his broader, yet frequently overlooked, impact on India’s burgeoning post-independence architectural landscape. While Chandigarh remains his most recognised achievement, the revelation of Jeanneret’s extensive involvement in numerous other architectural and urban planning projects across India considerably expands our understanding of his legacy. This demonstrates that his unique blend of modernist principles with local context and materials was not confined to a single, high-profile commission but was consistently applied across diverse, often less visible, projects. This broader footprint solidifies his independent vision and immense, lasting impact on India’s modern identity, confirming that his influence was far more pervasive than commonly acknowledged.

The Art of the Everyday: Jeanneret’s Furniture as Embodied Philosophy

The very premise of this exploration posits that Pierre Jeanneret’s contributions transcended mere functionality, demonstrating an immense artistic sensibility. Indeed, his furniture pieces were more than furniture; they are a confluence of functionality and art. Jeanneret articulated his furniture as an extension of his architectural principles, emphasising function while simultaneously pursuing a purity of lines and a geometrical sense of space. This dual emphasis resulted in designs that were simple yet sophisticated, reflecting the modernist ethos of functionality fused with aesthetic clarity. The consistent description of Jeanneret’s furniture as embodying functionality fused with aesthetic clarity and being an extension of his architectural principles indicates a truly integrated artistic philosophy. For Jeanneret, utility was not a limitation but a fertile ground for artistic exploration. The simple yet sophisticated and purity of lines and a geometrical sense of space in his designs elevate the mundane to the meaningful. This is an immense artistic statement: that true art can reside within the most utilitarian objects, transforming everyday items into expressions of beauty and intellectual rigour. It challenges the traditional hierarchy between fine art and applied art, asserting that thoughtful design inherently possesses artistic merit.

The poetry of materials in Jeanneret’s work was a deliberate artistic choice, prioritising inexpensive, locally-sourced teak, which was bug and humidity-resistant. He masterfully incorporated other indigenous materials such as bamboo, iron rod, rope, caning, cotton, and upholstery. Crucially, these designs were executed by local craftsmen, with the core expressive structural logic derived almost entirely from the local, traditional ways of working wood by hand. His innovation lay not in imposing foreign aesthetics, but in building on the local joinery techniques and material strengths of the wood. The eco-friendly origin of the Chandigarh chairs, crafted from trees harvested during the city’s construction, further underscores his pioneering commitment to sustainability. Jeanneret’s material choices—local, affordable, and climate-appropriate teak and cane—were not merely pragmatic but represented an immense artistic and ethical stance. By integrating indigenous craftsmanship and joinery techniques, he wove the local culture, economy, and environmental context directly into the fabric of his designs. This eco-friendly origin and his foresight in sustainable and contextual design long before these concepts became mainstream, demonstrate an artistic vision that transcends mere form to embody environmental and social responsibility. The poetry of materials thus becomes a poetry of place, purpose, and people, making his furniture a tangible manifestation of a responsible, integrated modernism.

His furniture pieces became iconic expressions of form and feeling:

- The “Kangaroo” Chair: A masterpiece of playful geometry, distinguished by its low height and angular design. Its distinctive “Z” shape, formed by three triangular co-planar elements, encourages a comfortable, relaxed yet attentive posture. Crafted from solid wood (ash, walnut, or black finish) with a handwoven rattan/cane seat and back, it harmonises ergonomically with the human body. Originally designed for the General Hospital Hall, its aesthetic appeal has seen it grace numerous private homes.

- The “Floating Back” Chair: A visually striking design, defined by its airy, suspended backrest that defies gravity. This unique feature provides ergonomic support while introducing a sense of lightness and transparency to the structure, embodying the ideals of transparency and openness of Chandigarh’s Modernist architectural structures. Constructed from solid wood with a woven rattan/cane seat and back, its sleek lines and minimalist silhouette offer a sophisticated aesthetic, making it versatile for various settings beyond the dining room.

- The “Easy” Chair: The epitome of relaxation, conceived for residential spaces. Its reclined back and spacious seat invite occupants to unwind, showcasing a seamless blend of comfort and aesthetic appeal. Typically rendered in dark teak wood and cane, it exemplifies Jeanneret’s mastery of design language and his commitment to enhancing the quality of daily life.

A consistent presence in his work is the “V-leg construction,” a distinctive feature first seen in his earlier Scissor chairs and extensively used in Chandigarh. Furthermore, Jeanneret is best known for his Minimalist seating furniture—often constructed without the use of fasteners. The consistent presence of “V-shaped legs” and the pioneering fastener-less construction in Jeanneret’s furniture are not merely technical specifications but immense artistic statements. These elements reflect a truly committed approach to structural honesty and visual lightness. The V-legs, for instance, transcend simple support to become dynamic, almost sculptural forms that define the chair’s silhouette. The absence of visible fasteners speaks to a purity of form and material, allowing the intrinsic beauty of the wood and the integrity of the craftsmanship to be fully appreciated. This approach elevates the functional aspects of construction into a deliberate aesthetic choice, making the very structure of the object a work of art, and perfectly embodying the modernist tenet of “form follows function” with an added layer of poetic and minimalist expression.

A core tenet of Jeanneret’s philosophy was the democratisation of design. Many of his pieces for Chandigarh were intentionally crafted to be easily reproducible and affordable. This reflected his unwavering commitment to creating quality design for all, not just the elite, a powerful social statement embedded within his artistic output. Jeanneret’s explicit aim for easily reproducible and affordable designs for public institutions and all social classes represents a powerful artistic and social declaration. In an era where high design often remained the preserve of an elite few, Jeanneret’s dedication to quality design for all imbued his work with a truly democratic ethos. This makes his furniture not just aesthetically pleasing objects but also tangible symbols of a progressive, inclusive vision for modern society. The artistic sensibility here extends beyond the mere form to encompass the intent and impact of design on the daily lives of a broad populace, positioning his work as a form of applied social art that truly shaped the environment for the common person.

Echoes in the Contemporary: Jeanneret’s Lasting Resonance

For decades, Jeanneret’s Chandigarh furniture unobtrusively served its functional purpose, unnoticed beyond the city. By the 1980s, much of it was tragically discarded, sold as scrap, or even burned in India, perceived as obsolete remnants of a bygone era. However, a dramatic re-evaluation began in the 1990s and early 2000s, when discerning French gallerists and international collectors discovered the treasure trove. These pieces now fetch jaw-dropping prices at prestigious auction houses, with some chairs selling for over $50,000 each, and an illuminated library table fetching $301,000. Their timeless elegance and craftsmanship has led to their appearance in the homes of global celebrities, cementing their status as coveted design icons. The astonishing transformation of Jeanneret’s furniture from discarded junk to highly coveted collector’s item and high-value auction pieces is a powerful commentary on the subjective nature of artistic valuation and the role of re-contextualisation. It suggests that the inherent artistic qualities of these objects were always present, but their recognition was delayed until they were filtered through a Western, high-design lens. This phenomenon raises critical questions about cultural ownership, the commodification of design, and the often-ironic journey of utilitarian objects into the realm of fine art, making the furniture a poignant symbol of a complex post-colonial design heritage.

The enduring global appeal of Pierre Jeanneret’s designs finds a distinct resonance within Australia’s interior design industry, particularly in Sydney, where his pieces are embraced for their timeless aesthetic and inherent blend of functionality and art. Licensed reproductions by Cassina, such as the iconic Capitol Complex Armchair and various Commercial and Easy Chairs, are readily available through local distributors like Mobilia, making them accessible to designers for high-end projects. This accessibility has led to their integration into sophisticated Australian spaces, as evidenced by Alexander & Co.’s Sydney offices, which feature Jeanneret ‘Easy’ teak chairs to create a harmonious blend of residential artistry within a commercial setting. Similarly, Greg Natale has incorporated the Cassina 053 Capitol Complex armchair into his luxurious North Bondi residential project, demonstrating how Jeanneret’s designs complement a layered, referential aesthetic that values iconic and historically significant pieces. This demonstrates a clear place for Jeanneret’s influence, with Australian designers leveraging his work to imbue spaces with a raw, radical, and inherently humanistic modernism that aligns with contemporary trends favouring natural materials, craftsmanship, and a seamless blend of old and new.

Jeanneret’s pioneering work in Chandigarh is now widely recognised as a pioneering example of sustainable and contextual design. His holistic, site-specific, and socially conscious approach, which was ahead of his time, continues to inspire designers today in an era increasingly focused on environmental responsibility. The emergence of a thriving replica industry in Indian cities like Mumbai and Jaipur signifies a renewed local appreciation and efforts to make the designs more accessible, echoing his original commitment to the democratisation of design. Jeanneret’s design principles, particularly his emphasis on local materials, indigenous craftsmanship, and climate-responsive architecture and furniture, were indeed ahead of his time. In the current global climate, where sustainability and cultural relevance are paramount, his work transcends historical importance to become prophetically modern. The growth of a replica industry in India is a notable ripple effect, suggesting that the original democratic and accessible intent of his designs is being re-embraced, even as the originals become luxury items. This solidifies his legacy as a designer whose artistic vision was truly intertwined with ethical and environmental considerations, offering a timeless blueprint for responsible and culturally integrated design.

Perhaps the most poignant testament to his impact comes from Jeanneret himself: “The working methods that I discovered in India finally taught me self-esteem after so many failures in France. Chandigarh was for both of us a kind of glade in the human jungle”. This keenly personal revelation speaks volumes about the transformative power of his work in India. His self-designed house in Chandigarh, now a museum, stands as a physical embodiment of his lasting presence and contribution, allowing future generations to connect with the human story behind the iconic designs. Jeanneret’s keenly personal reflection on finding “self-esteem” and describing Chandigarh as a “glade in the human jungle” reveals that his artistic and functional contributions were not merely professional achievements but an immense journey of personal and spiritual fulfilment. This narrative transforms his designs from inert objects into symbols of human resilience and purpose. The decision to convert his Chandigarh home into a museum further solidifies this legacy, allowing visitors to experience the intimate connection between the man and his work, bridging the gap between design and biography, and making his contributions a universal testament to the human spirit’s capacity for creation and self-discovery.

The Subtle Dialogue Continues

Pierre Jeanneret, often referred to as a humble genius, may have operated for much of his career in the shadow of his more famous cousin, Le Corbusier, but his work was undeniably raw and radical. His true artistic compass was guided by experimentation rather than success, leading to designs that consistently transcended mere utility. His oeuvre expresses a rich ambivalence between the rational and spiritual, a testament to a designer who saw beyond the blueprint, imbuing every line and joint with deeper meaning.

Jeanneret’s Chandigarh chairs and buildings stand as a monument to the visionary spirit of mid-century modern design. He seamlessly merged beauty with utility and redefined living and working spaces, creating a legacy of innovation and creativity that resonates globally. The Chandigarh chair, in particular, serves as a palimpsest of India’s modernist dreams, its cultural blind spots, and its evolving relationship with heritage. It is a tangible reminder that true art can be found not just in grand gestures, but in the thoughtful, empathetic crafting of the everyday, a subtle dialogue between the practical and the poetic that continues to echo through time. Jeanneret’s brilliance lies in his unique ability to infuse the pragmatic demands of modernism with an immense artistic and humanistic spirit. His raw and radical approach, driven by experimentation rather than success, allowed him to create objects that were simultaneously highly functional and truly evocative. The rich ambivalence between the rational and spiritual in his work is the very essence of his artistic sensibility. His designs, especially those for Chandigarh, are not merely functional objects but immense cultural artefacts that tell a complex story of nation-building, cross-cultural exchange, and the lasting power of design to shape lives and environments. This positions him not just as a designer, but as a subtle revolutionary who redefined the very soul of modernism, proving that utility can be truly artistic, and art can be truly useful.

Further Reading

Seguin, Patrick. Le Corbusier & Pierre Jeanneret: Chandigarh, India. Galerie Patrick Seguin, 2014.

Bahga, Sarbjit, and Bahga, Ravinder Kumar. Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret: The Indian Architecture. Prakash Books, 2014.

Fondation Le Corbusier. Official Website. Accessed June 4, 2025.

Artnet. “Pierre Jeanneret.” Artist Biography & Works. Accessed June 4, 2025.

Bauhaus Kooperation. “Pierre Jeanneret: The Forgotten Architect of Chandigarh.” Accessed June 4, 2025.