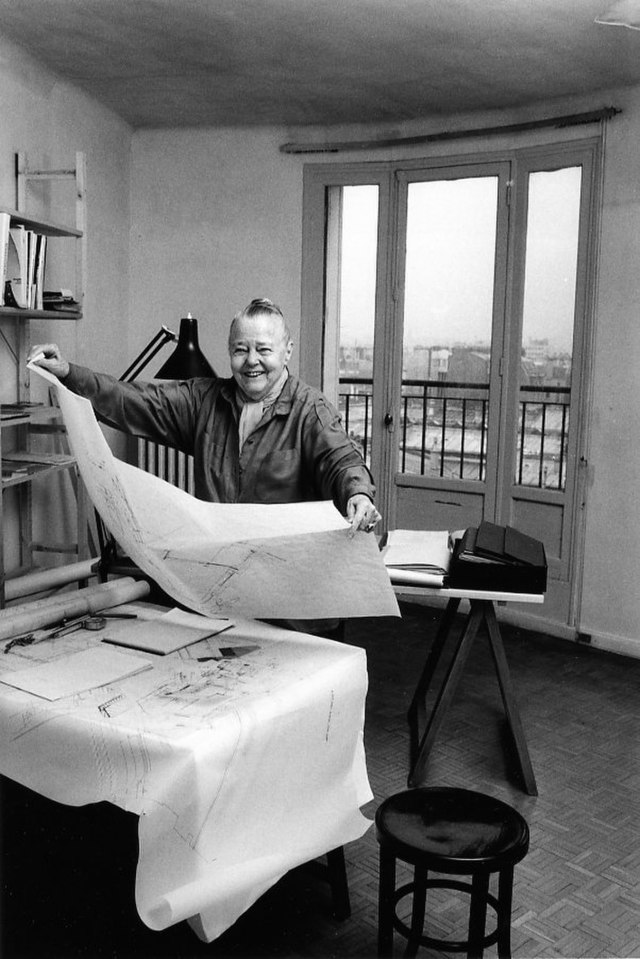

Charlotte Perriand, photographed in 1991.

Photo by Robert Doisneau, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

In the annals of 20th-century design, certain figures cast long, indelible shadows. Le Corbusier, Jean Prouvé, Pierre Jeanneret – their names echo with the force of architectural revolution. Yet, often standing just beyond the immediate glare of the spotlight, a force equally profound, equally transformative, shaped the very fabric of modern living. Charlotte Perriand, a name synonymous with innovation, humanism, and an unwavering belief in design as a tool for social betterment, redefined the domestic landscape, crafting environments that were at once functional, beautiful, and deeply resonant with the human spirit. Her legacy, far from being confined to dusty archives, continues to inspire, challenging conventional notions of space, material, and purpose.

The Genesis of a Modernist: Parisian Roots and Early Audacity

Born in Paris in 1903, Charlotte Perriand emerged from a household steeped in creativity, her parents skilled craftspeople within the city’s haute couture industry. This early exposure to meticulous craftsmanship and the nuanced language of design undoubtedly shaped her nascent artistic sensibilities. Her formative years were also punctuated by frequent trips to Savoie, hinting at a lifelong connection to nature and the mountains that would later define much of her most ambitious work. Her formal education commenced in 1920 at the École de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, where she embarked on a rigorous five-year course in furniture design. She quickly distinguished herself, her innate talent recognised by instructors who selected her to exhibit at various Parisian decorative art expositions. By 1925, she was already showcasing her designs at the prestigious International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, a testament to her precocious vision.

Despite her grounding in traditional decorative arts, Perriand swiftly pivoted, distancing herself from the ornate fabrics, floral motifs, and conventional wood that characterised the prevailing aesthetic. Her fascination lay instead with the burgeoning machine age, finding immense inspiration from the sleek lines and industrial precision of airplanes and automobiles. She began experimenting boldly with materials previously considered antithetical to domestic warmth: tubular steel, aluminum, and chrome. A powerful declaration of her radical vision, in 1926, a mere year after graduation and marriage, she transformed her own attic apartment into a machine age interior. This personal laboratory became a precursor to her public statements, showcasing a sincere personal conviction and foresight that challenged traditional notions of domesticity. This rapid and decisive embrace of industrial aesthetics was not merely a stylistic choice but a philosophical one, aligning with the ethos of an era fascinated by efficiency and modernity.

In 1927, Perriand unveiled “Bar sous le Toit” (Bar Under the Roof) at the Salon d’Automne. This installation, featuring tubular steel furniture and an aluminum and chrome bar, was a provocative and avant-garde declaration of her talent, impressing critics and, crucially, a certain Le Corbusier. Her ambition then led her to apply to Le Corbusier’s esteemed studio in 1927, only to be met with the infamous, dismissive retort: “We don’t embroider cushions here,” as she often recounted. Undeterred by this patriarchal barrier, Perriand invited him to witness her “Bar sous le Toit.” Le Corbusier, reportedly “spellbound” by her innovative work, hired her on the spot as a furniture and interiors specialist alongside his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret. This act of defiance and confident self-presentation forced him to confront his own biases and recognise her undeniable talent, marking a pivotal moment that set the stage for her later humanising influence on a male-dominated architectural movement.

Three Fingers on One Hand: Forging the Icons of the Machine Age

From 1927 to 1937, Perriand became an indispensable force within the studio of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. She famously described their collaborative work as “three fingers on one hand,” a powerful metaphor for the integrated and symbiotic nature of their partnership, challenging the common perception of her as a mere subordinate. Le Corbusier himself acknowledged her vital role, writing in a 1932 letter that the “entire responsibility” for realising the “domestic equipment” of his buildings was hers, praising her “exceptional qualities of inventiveness, initiative and realisation in this domain.” Perriand noted that Le Corbusier “waited impatiently for me to bring the furniture to life”. This dynamic was not merely a collaborative effort but a necessary synergy. Le Corbusier provided the grand theoretical framework of “furniture as equipment” and the “machine for living,” but it was Perriand who imbued these concepts with the essential human element – comfort, tactility, and livability – making them commercially viable and widely influential.

Together, they embarked on the innovative project for “l’équipement d’intérieur de l’habitation” – literally, “living equipment.” This concept redefined furniture not as decorative objects but as functional, adaptable machines for living, integral to the architectural space. Their aim was to create functional living spaces, underpinned by Perriand’s firm conviction that better design could foster a better society. This project introduced a revolutionary idea of living as something free and relaxing, a departure from the rigid, ornate interiors of the past. Perriand’s genius lay in translating Le Corbusier’s theoretical “furniture as an extension of the human body” into tangible, comfortable realities.

The collaboration yielded some of the 20th century’s most lasting design classics. In 1928, they designed three seminal chairs: the LC2 Grand Confort armchair, the B301 reclining chair, and the iconic B306 chaise longue. The LC4 Chaise Longue, conceived as a machine for relaxation, was revolutionary for its ergonomic principles and futuristic aesthetic. Perriand’s distinct contributions to these pieces were pivotal: she introduced the adjustable frame and headrest cushion for maximum comfort, and crucially, integrated sensual elements like leather and cowhide, adding tactile warmth to the industrial tubular steel. Beyond these, the collaboration produced a comprehensive suite of “LC” series pieces, including the LC1, LC3, LC5, LC6, LC7, LC8, LC9, LC10 P, LC11 P, LC12, and LC13. While often solely attributed to Le Corbusier, it is now widely recognised that Perriand was the real genius behind them, bringing the designs to life. Her LC7 chair, designed for her own apartment, and her prototyping of the LC3 sofa when her male counterparts couldn’t agree on details, underscore her practical ingenuity and vision. Perriand’s presence was essential in humanising Le Corbusier’s often austere and rigid architectural visions, infusing them with warmth, practicality, and a keen sensitivity to interior space design. This period of collaboration, often historically misattributed, underscores a broader pattern of women’s intellectual and creative contributions being absorbed or downplayed within male-dominated fields. Recognising Perriand’s true agency in this partnership is crucial for a more accurate and equitable understanding of modernist design history.

A World of Influence: From Industrial Rigor to Organic Warmth

By the late 1930s, Perriand began to consciously distance herself from the strict, industrial aesthetic that had characterised her early work. Her evolving philosophy embraced organic forms and natural materials, a shift influenced by her travels and collaborations with artists like Fernand Léger. She started exploring free-form carving, designing a curved table for herself in 1938. Her famous declaration, “Wood is made for caressing and can be as soft as a woman’s thighs,” encapsulates this newfound sensuality and appreciation for material warmth, contrasting sharply with the cold precision of tubular steel. She began incorporating wood, cane, and stone into her designs, moving beyond the rigidity of industrial modernism.

A pivotal turning point came in 1940 when Perriand sailed for Japan, invited by the government as an advisor on industrial design. Here, she immersed herself in traditional design techniques and collaborated with local artisans. Her time in Japan substantially influenced her work, leading to a unique synthesis of Eastern aesthetics and Western modernism. She discovered the inherent simplicity of Japanese interiors, their modularity, and their economical, functional approach to space. This immersion, combined with the practical constraints and opportunities of wartime, solidified her shift towards organic forms and a heightened appreciation for craftsmanship and natural resources. This personal and professional transformation directly fueled her post-war commitment to design for the masses.

During World War II, she was forced to leave Japan as an “undesirable alien” but became trapped by a naval blockade, spending the remainder of the war in Vietnam. This period further exposed her to local craftsmanship and materials like bamboo, which would later feature prominently in her designs. It was also in Vietnam that she married her second husband and gave birth to her daughter, Pernette, adding a profoundly personal dimension to this transformative period. Upon her return to France in 1946, her career was revived, marked by a renewed collaboration with Jean Prouvé and a design language enriched by her Asian experiences, incorporating bamboo, weaving, and lacquer.

Post-war, Perriand’s work increasingly focused on designing for the masses, aligning with her socialist convictions. She contributed to large-scale housing projects, notably designing interiors for Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille. She firmly believed that architecture and design should be accessible to most people, championing design as a fundamental tool for social progress. This commitment manifested in her development of low-cost prefabricated mountain shelters, making holidays in nature available to a wider audience. Her designs often embraced the concept of “minimal space,” prioritising functionality, economy, and harmonious integration with surroundings. She was remarkably prescient, envisioning green roofs and buildings that blended seamlessly into the landscape long before these concepts became mainstream.

After World War II, Perriand forged a formative partnership with Jean Prouvé. This collaboration saw her combine the precise lines of Prouvé’s bent steel with the soft, round edges and warmth of natural wood, creating modernist furniture that balanced industrial efficiency with material tactility. She experimented extensively with folded sheet steel, which she termed the new hardware, an inexpensive and flexible alternative to aluminum and tubular steel that Prouvé had introduced to her. Their joint efforts produced various shelf and storage products, as well as temporary housing solutions for the post-war era. Perriand’s journey from European modernism to an Asian-influenced, human-centred, and environmentally conscious design pre-dates many contemporary movements. She was an early pioneer of sustainable design and cross-cultural integration, demonstrating a remarkable foresight that continues to resonate today, highlighting how personal experiences can profoundly shape a visionary’s professional philosophy.

Crafting Environments: Major Projects and Holistic Visions

In the post-war era, Perriand applied her evolving principles to an impressive array of large-scale public and residential commissions. Her continued commitment to functional, efficient living was notably evident in her design of a prototype kitchen for Le Corbusier’s groundbreaking Unité d’Habitation apartment building in Marseilles. Beyond this, her collaborative spirit soared across diverse sectors: she worked with Fernand Léger on the design of the Hôpital Saint-Lo and contributed to the League of Nations building for the United Nations in Geneva. Her international reach expanded further through partnerships with Le Corbusier and the Brazilian architect Lucio Costa on the interior of their Maison du Brésil at Cité Universitaire in Paris, and with Erno Goldfinger on the French Tourist Office in London’s Piccadilly. These projects underscored her versatile application of design as a tool for progress, from the intimate domestic sphere to major public institutions.

A pivotal project embodying her mature design method was the ‘Tunisie’ bookcase, commissioned in 1952 for the Maison de la Tunisie at the Cité Universitaire in Paris. This piece emerged from the Group Espace, an initiative aimed at synthesising arts and creating animated urban spaces. Perriand led a group that included artists Sonia Delaunay, Nicolas Schöffer, and Silvano Bozzolini, with manufacturing by Ateliers Jean Prouvé. The bookcase showcased her mastery of the volumetric measure of space, a principle of spatial harmony refined during her time in Japan. It incorporated elements developed earlier in her career, such as stacked block formations and sliding doors, but with new materials like pine, sapele mahogany, painted steel, and diamond-point embossed aluminum. Her experimentation with Prouvé’s new hardware – folded sheet steel – was central to its innovative structure. The rhythmic, Mondrian-like colour scheme, involving all group members, further underscored the synthesis of the arts ethos. The ‘Tunisie’ bookcase is a microcosm of her mature philosophy, blending industrial efficiency with the warmth of natural wood and the vibrancy of integrated colour. This project, alongside her work on public commissions, concretely demonstrates her commitment to design for the masses and improving everyday life.

Beginning in 1962, Perriand embarked on the largest and longest project of her career: designing a series of ski resorts in Savoie, a monumental undertaking that consumed her until 1985. This was a dream realised, combining her abiding love of design with her passion for mountains and nature. At Les Arcs, her vision of integrating architecture seamlessly into the landscape came to full fruition, characterised by gently sloping buildings that respected the natural topography. The interiors were conceived with serial, pre-produced, modular furniture, allowing for efficient, comfortable apartments with direct mountain views through large bay windows. This ambitious project accommodated 30,000 people across three altitudes (1600, 1800, 2000 meters). While collaborating with architects like Gaston Regairaz and engineers including Jean Prouvé, Perriand unequivocally took the creative lead, orchestrating a truly holistic environment. Les Arcs, as the culmination of her career, is the ultimate expression of her “art of living” philosophy, integrating nature, community, and functional design on an unprecedented scale.

Perriand’s political dimension in architecture was evident in her efforts to redefine women’s relationship with domestic space. She pioneered the design of open kitchens adjoining living rooms, a revolutionary concept intended to literally and symbolically free housewives from isolation. This design choice allowed women to participate more fully in the social life and conversations within the home, advocating for freedom of movement and breaking down the traditional confinement of the kitchen. Her deliberate design of open kitchens is a clear example of how she used design to challenge traditional gender roles and foster a more communal, equitable domestic life, proving that her principles extended beyond aesthetics to social reform. Perriand’s holistic vision, honed through her diverse experiences and collaborations, allowed her to tackle projects of monumental scale and complexity, demonstrating that her principles of functionality, modularity, and human-centric design were applicable across various contexts, from individual furniture pieces to entire urban environments. Her unwavering political convictions, particularly her socialist leanings and belief in accessibility, directly translated into practical design solutions for mass housing and public spaces, making her a truly engaged artist.

Enduring Resonance: A Legacy for the Future

Charlotte Perriand, often referred to as an “Unsung Heroine of Design,” tirelessly worked to break through the conventionalism of her time. Her bold creations caused a sensation, yet her contributions were frequently overlooked in historical narratives, particularly in contrast to her male counterparts. Many of her iconic designs, now considered modern classics, were frequently attributed solely to Le Corbusier, despite her being the real genius behind them. Her pioneering spirit and unwavering belief that “the key thing for a woman is her freedom, her independence. Being at the top of what she is doing,” resonate powerfully with contemporary conversations about the roles of women in society. The continuous production of her pieces by Cassina and the proliferation of major retrospectives are not just celebrations of a historical figure, but powerful affirmations of her timeless relevance.

Charlotte Perriand’s legacy is palpably felt within Australia’s contemporary interior design industry, where her foundational principles and iconic furniture pieces are actively embraced. Leading Australian design firms, such as Fiona Lynch Interior Design, have incorporated her elegant chairs into residential projects like the Elsternwick House, while Flack Studio prominently featured Perriand’s Table Monta in the design of the Cassina Sydney showroom. This direct engagement is facilitated by the continued availability of her work in Australia; her timeless designs are officially sold through premier retailers like Mobilia, with showrooms across Perth, Melbourne, and Sydney, offering an extensive range from the LC series chairs and sofas to the distinctive Tabouret stools and Nuage storage units. Additionally, the Cassina Store Melbourne further solidifies her presence, and CULT Design has hosted exhibitions showcasing her work, including a notable visit by Perriand’s daughter, Pernette Perriand-Barsac, signaling a deliberate effort to promote and celebrate her enduring influence within the Australian design landscape.

Despite being designed over 90 years ago, Perriand’s furniture continues to transcend modern trends. As early as 1962, L’Expresse magazine asserted that her “thirty years of furniture… will last for centuries,” a prophecy proving remarkably accurate. Her visionary design approaches remain highly relevant today. Her revolutionary user-centric approach, emphasising human needs and ergonomic design, anticipated the user-centred methodologies that define contemporary architecture and interior design. Her projects frequently incorporated modular elements, allowing for customisation and adaptability, reflecting a foresight into evolving human needs. Her ecological foresight, evident in her early advocacy for green roofs and buildings that blended seamlessly into the landscape, speaks directly to current concerns about sustainability and the harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. Her holistic approach, integrating art, nature, and an active lifestyle within a single dwelling, continues to inspire.

Perriand’s work has been the subject of numerous major retrospectives, including at the Musée des Arts-Décoratifs in Paris (1985), the Design Museum in London (1998 and the acclaimed “The Modern Life” in 2021), and the Fondation Louis Vuitton (“Inventing A New World”). The Kunstmuseen Krefeld is dedicating the first retrospective in the German-speaking world to her in 2025, titled “L’Art d’habiter. The Art of Living”. Her notable contributions earned her prestigious accolades, including the Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres (1981) and the Légion d’Honneur (1983). Her autobiography, Vie de Création (Life of Creation), published in 1998, offers a vital first-person account of her groundbreaking journey. Charlotte Perriand passed away in Paris in 1999, leaving behind a pioneering spirit and progressive vision that continues to inspire designers, architects, and creatives worldwide.

A Timeless Blueprint for Living: Designing a Better World

Charlotte Perriand’s journey through the 20th century was not merely that of a designer of objects, but of an architect of experience, a visionary who understood that the true art of living lay in the seamless integration of form, function, and human wellbeing. From her audacious embrace of the machine aesthetic in early Parisian salons to her remarkable synthesis of Eastern philosophies and Western modernism, and ultimately, to her monumental, human-centric alpine resorts, Perriand consistently pushed the boundaries of what design could achieve.

Her life’s work serves as a powerful counter-narrative to the often-singular focus on male “masters” of modernism. Her legacy is a testament to the idea that true innovation lies not just in aesthetic form, but in how design serves humanity, fosters connection with nature, and promotes social equity. Her ability to balance bespoke artistry and large-scale production and her unwavering commitment to practicality without compromise demonstrate a pragmatic genius that sought both quality and accessibility, ensuring her work’s widespread impact and continued inspiration for future generations of designers. Perriand’s continued relevance stems from her holistic, human-centered, and socially conscious approach, a methodology that anticipated many contemporary design concerns. Her “unsung heroine” status highlights a broader historical pattern of women’s intellectual and creative contributions being marginalised in male-dominated fields, making her current widespread recognition a crucial and overdue re-evaluation. In an era increasingly concerned with sustainability, user experience, and the social impact of built environments, Charlotte Perriand’s pioneering spirit offers not just historical precedent, but a timeless blueprint for a better-designed world.

Further Reading

Perriand, Charlotte. Charlotte Perriand: A Life of Creation. The Monacelli Press, 2003.

McGuirk, Justin. Charlotte Perriand: The Modern Life. Thames & Hudson, 2021.

Perriand, Charlotte, et al. Living With Charlotte Perriand. Skira, 2019.

Barsac, Jacques. Charlotte Perriand: Complete Works, Volume 4: 1968–1999. Scheidegger & Spiess, 2020.

Design Museum. “Charlotte Perriand.” Accessed June 4, 2025.